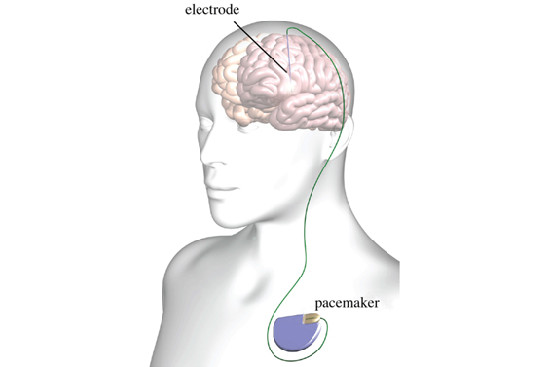

Parkinson's treatment with deep brain stimulation (brain pacemaker)

* image source

The historically correct road to the discovery and development of deep brain stimulation

In the discussion about the doubtful relevance of animal experiments and their contribution to modern medical achievements, proponents refer to supposed flagships of animal-based research. But a closer look reveals a picture of medical research that leads to success without animal testing.

Deep brain stimulation is an extremely popular example among animal experimentation advocates. It is claimed that the successful treatment of Parkinson's patients with deep brain stimulation would not have been possible without pioneering animal studies. But medical history paints a different picture! Decades before animal experimenters administered the neurotoxin MPTP to monkeys to induce symptoms of Parkinson's disease, the method of deep brain stimulation and its physiological basis were explored and developed through studies in humans. Parkinson's disease is a chronic and progressive medical condition that has yet to be cured successfully. Deep brain stimulation can provide relief from some of the symptoms. Movement disorders are alleviated with the help of electrodes that are inserted into the patient’s brain and then used to stimulate a brain region (the basal ganglia) responsible for movement control. The treatment method is therefore also colloquially referred to as a “brain pacemaker”.

However, it is also important to emphasize that Parkinson's disease is much more complex, and that deep brain stimulation cannot stop its progression. Other symptoms such as memory loss, anxiety, and depression still require further treatment. Despite the undeniable successes of deep brain stimulation, this method is not without risks. Serious side effects such as fatal cerebral hemorrhage are three times more common compared to conventional medical treatment (Deuschl et al. 2006; Weaver et al. 2009).

Nevertheless, the success of deep brain stimulation is non-controversial. It is therefore worth taking a closer look at this success story. It becomes clear that the often-cited experiments on the "MPTP monkey model" were not aligned with medical progress, and that the development of deep brain stimulation is based on the work of visionary researchers with human patients.

The beginnings in the 19th century

It all began in 1874 when the scientist Robert Bartholow first gained insight into electrical brain stimulation in humans. (1)

In 1882, neuropsychiatrist Enzio Sciamanna performed a series of systematic experiments with electrical stimulation on patients with craniocerebral trauma. (1) In 1883, surgeon Alberto Alberti carried out research on cerebral stimulation over a period of 8 months on a woman suffering from a brain tumor. (1) In 1890, neurosurgeon Victor Horsely performed the first surgeries to treat movement disorders. (2)

Further progress in the 20th century

In 1938, Vittorio A. Sirioni described the first modern therapeutic use of brain stimulation in severe psychosis. (1)

1939/1966 Paul Bucy and Walter Edward Dandy warned against operations on the basal ganglia, because Dandy suspected the seat of consciousness was located there, and Bucy reported on paralysis and other serious complications. These claims were rebuked by a report by T.J. Putnam in 1966. Putnam had found that cutting out the caudate nucleus (part of the basal ganglia) relieved the symptoms of Parkinson's patients without causing the feared complications (paralysis, unconsciousness). (2)

1947/1950 The stereotactic surgical methods were refined by using so-called atlases of human brains, which were developed using cadavers. Precise operations in three-dimensional space became possible. (Ernst Spiegel et al. 1947, Henry Wycis 1950) The electrical stimulation that was used intraoperatively to localize the deep brain structures suggested that this method could not only be used for diagnosis but also for therapy. This laid the foundation for the shift from destructive to stimulatory neurosurgery. (1)

1952 The scientist Jose M. Delgado was the first to describe the technique of implanting brain electrodes in humans and its importance for the diagnosis and therapy of patients with mental illnesses. The animal experiments he carried out at the same time, e.g. on bulls, did not lead to the desired results. (Delgado et al., 1952) (1)

1954/1956/1980 Deep brain stimulation was used to treat chronic pain and abnormal movements. (Heath 1954, Pool et al. 1956, Mazars et al. 1980) (2)

Successful subthalamic nucleus surgery was first reported in 1963, 20 years before the "monkey model"! O.J. Andy studied 50 Parkinson's disease patients, and identified the appropriate sites for tissue damage using high-frequency deep brain stimulation. (Andy et al. 1963) (2)

1965 Neurophysiologist Carl Wilhelm Sem-Jacobsen initially used implanted depth electrodes to record brain activity and stimulate patients with epilepsy or psychiatric disorders. He successfully implanted multiple electrodes in the thalamus, and was able to identify the brain area best suitable for surgical tissue damage in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. The electrodes often remained in the patient for months without any side effects. (Sem Jacobsen, 1965)

Reports of chronic brain stimulation with electrodes implanted in the thalamus for the treatment of chronic pain (Y.Hosobuchi et al., 1973) and in vegetative patients (R. Hasserl et al., 1969) were published in the early 1970s (1)

In 1968, L-Dopa was discovered as a drug therapy for Parkinson's disease, and temporarily replaced surgical procedures. However, it soon became apparent that not all patients responded to L-Dopa. (1)

1972/1975 further studies showed the therapeutic effect of deep brain stimulation in movement disorders. (Natalia P. Bechtereva et al. 1972, 1975) (1)

In the 1970s/1980s, ever smaller, more powerful, and biocompatible cardiac pacemakers were developed in the field of cardiology. The experience gained from this technique was transferred to deep brain stimulation, and led to electrodes that could be permanently implanted. (2)

In 1978, the American neurosurgeon Irving S. Cooper presented encouraging results in the treatment of cerebral palsy, spasticity, and epilepsy using deep brain stimulation of the ventrolateral thalamus. He reported his excellent results treating over 200 patients with chronic cerebellar stimulation. (Cooper, 1978) (1) In 1987, A.L. Benabid introduced the idea of using chronic stimulation as a therapeutic method through his report on stimulation of the thalamic region. He showed that stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus resulted in improvement of Parkinson's disease. (Benabid et al., 1987) (1)

The role of animal experiments

In 1983, the so-called MPTP model for simulating Parkinson's disease was first described in monkeys. (Burns et al. 1983) It is based on the accidental discovery that the intoxicant MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) causes Parkinson's-like symptoms in drug addicts. Monkeys poisoned with MPTP show similar signs. (2)

In 1989/1990, researchers "demonstrated" the importance of the subthalamic nucleus in monkeys, in which Parkinson's disease-like symptoms were artificially and chemically induced. (Mitchell et al. 1989, Alexander et al. 1990, Bergmann et al. 1990) (2)

In 1993, Nobel laureate Francis Crick criticized the abuse of monkeys in brain research in an article entitled “Backwardness of human neuroanatomy” (Crick and Jonas 1993). (2)

Conclusion

- The success story of developing deep brain stimulation has been fueled by the intermeshing works of clinical research.

- Animal experiments have never contributed to the development of the method.

- Deep brain stimulation was already in use by the time animal experimenters established the often cited "MPTP monkey model".

- "New insights" from research on monkeys had already been known long beforehand.

19 September 2017

Christian Ott M.Sc., neurobiologist and Katharina Feuerlein, medical practitioner

* Shamir R, Noecker A and McIntyre C - Shamir R, Noecker A and McIntyre C (2014) Deep Brain Stimulation. Front Young Minds. 2:12. doi: 10.3389/frym.2014.00012 https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2014.00012, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44938894

Secondary sources

(1) Sirioni, Vittorio A.: Origin and evolution of deep brain stimulation. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 2011: 5 (42), 1-5

(2) Maxwell, Marius: offener Brief an Voice for Ethical Research at Oxford (VERO), http://www.vero.org.uk/Openletter.pdf